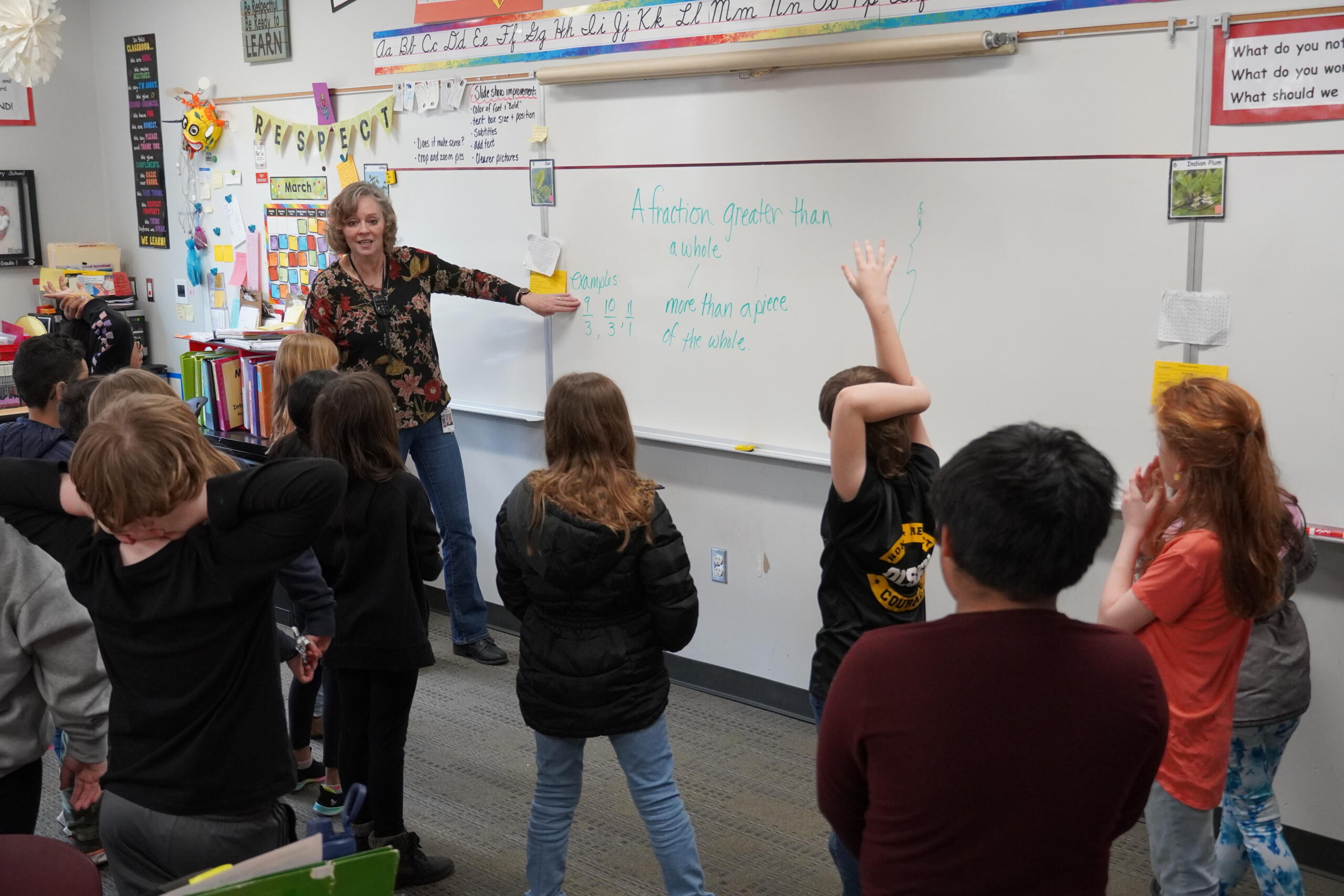

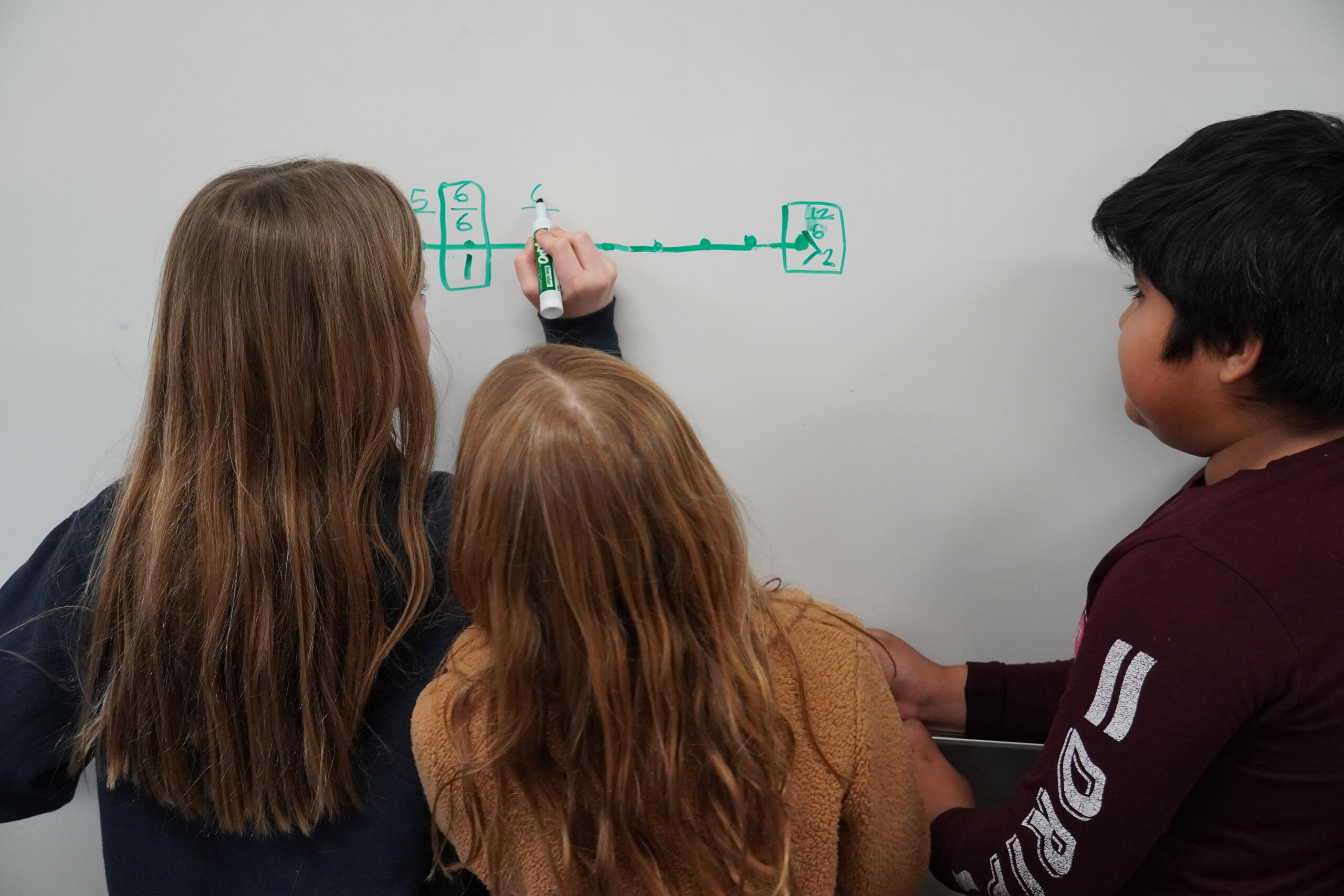

It’s all about staying focused, and staying engaged. Students in Mrs. Sande’s math class are almost always up and moving. It keeps them thinking.

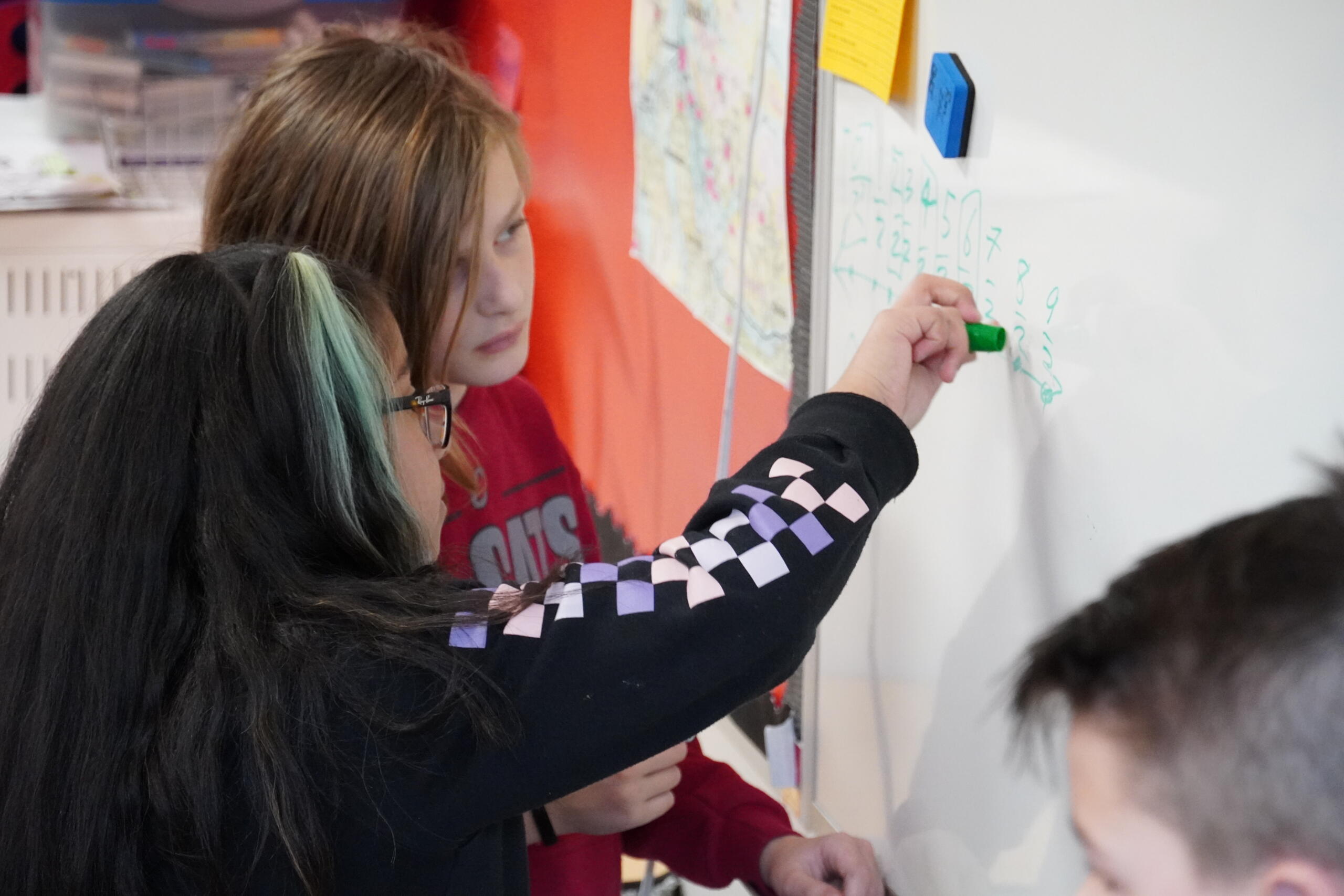

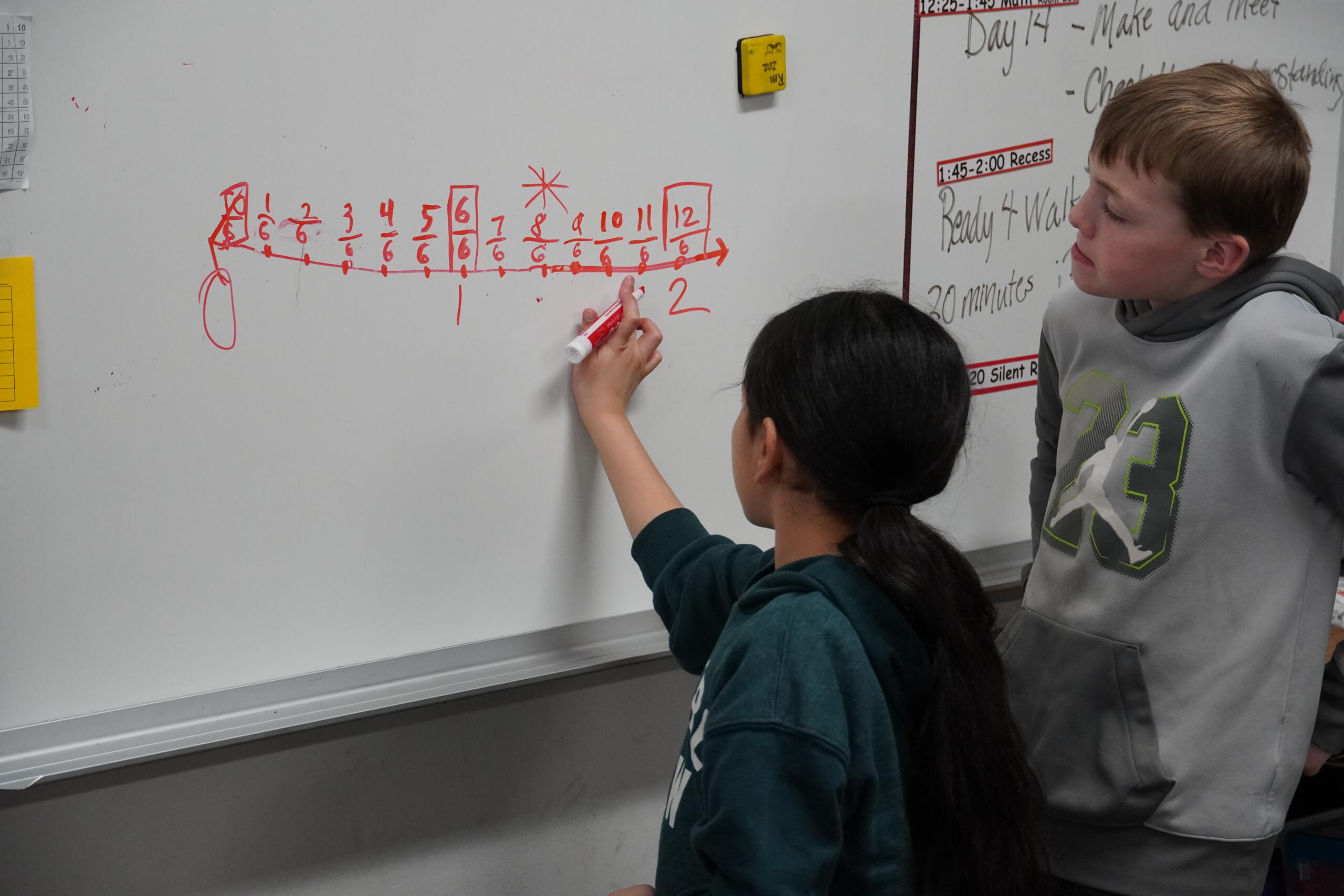

Researcher Peter Liljedahl has found that students sitting at their desks (or tables) and writing in their notebooks is not the best space for student thinking – and many teachers agree. What some Chehalis teachers are finding is most optimal is to have the students standing and working – in small groups, on white boards.

When they do sit down, it’s only after they have come together as a class for a little instruction – while standing.

When they are at their desks, they have a common task – “Write about what we did today in your math journals.” And they all are prepared for success. Everyone was engaged. Everyone participated. Everyone was thinking. Everyone had something to write about.

“It’s working,” says third-grade teacher Kelly Sande. “After 37 years of teaching, I’m eager and excited to find another proven strategy for keeping kids engaged.”

Sande, along with several other Chehalis teachers, is building what Liljedahl calls, Thinking Classrooms. Instructional strategies are carefully designed to keep students focused, and give them several ways to SHOW their understanding of math concepts.

Many of today’s parents learned basic formulas when they were in school, such as long division, to solve math problems. In those days, if you were “good at math,” you may have been good at memorizing algorithms, or formulas and remembered when best to employ that knowledge.

Math hasn’t changed. Two plus two still equals four. What has changed are some of the strategies teachers use when teaching about math. “With math, the goal isn’t just to know the correct answer anymore,” says Sande. “The goal is to ensure students develop a better conceptual understanding of what is going on in a math question. And conceptual pieces are different.”

“We used to practice a method called ‘I do. We do. You do,” she says. Using that strategy, only 20 percent of students were actually thinking.” She points out that when building Thinking Classrooms, the strategy is radically different. It’s “You all do (problems at the white board), then WE do, then YOU do. Lots of practice, done in the right order.

“And once they sit down, some students will get distracted again and have a hard time engaging,” comments Sande.

“Let’s all get up and get focused again.” After a short review, while many students fidget and move around as they listen, they return to their desks with a single purpose. And for a few more minutes, they work in their journals – showing their thinking.

To help students develop a good understanding of what is going on in math, teachers will often teach a number of ways to illustrate an underlying concept of a math problem. The language in the math classroom has changed. Now, you may hear teachers say things like:

Show what you know.

Make your thinking visible.

Draw pictures to illustrate how you got that answer.

Write about your solution in your math journal.

Check your understanding. Hand me your exit ticket.

The short visit in Mrs. Sande’s classroom didn’t reveal all that makes up a Thinking Classroom. The 14 teaching practices for enhancing learning take time to understand, and it takes time to plan for implementation. But at Orin Smith Elementary, Mrs. Sande is doing what she can – working hard to keep her students engaged and thinking and learning.

To read an executive summary of the 15 years of research Liljedahl has used, and better understand what makes up a Thinking Classroom, click here.

To see a middle school version of this strategy, read Building thinking classrooms.