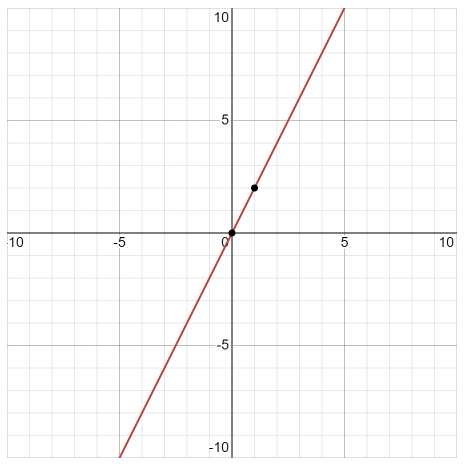

If called upon to create a graph of a linear function such as y=2x, how many adults would successfully recall instruction in their high school mathematics class?

Investigating long-ter m memory of knowledge learned in school is challenging and fascinating. Some researchers have determined that remembering math concepts you learn in high school strongly depends on the number, level, and total length of mathematics courses you take (2003, Karsenty). However, some current educators suggest that recall is highly influenced by the instructional strategies a math teacher uses.

m memory of knowledge learned in school is challenging and fascinating. Some researchers have determined that remembering math concepts you learn in high school strongly depends on the number, level, and total length of mathematics courses you take (2003, Karsenty). However, some current educators suggest that recall is highly influenced by the instructional strategies a math teacher uses.

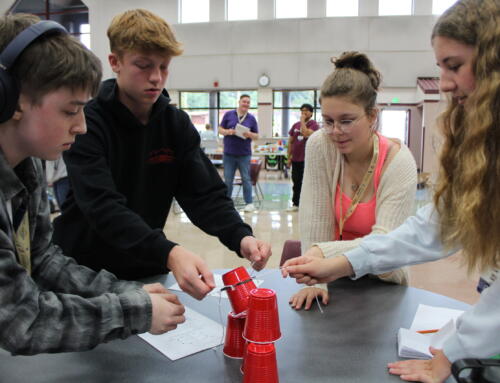

For example, over the last four years, teachers in Chehalis School District have been intentionally working on structured student talk, also known as mathematical discourse as a matter of routine. Mathematical discourse is more than simply talking about math. It is a set of tools and practices that make thinking visible. Chehalis educators know that how students talk about mathematics reflects in part what they understand about mathematics. “Discourse around meaningful math concepts is a fundamental way to build connections and develop deep understanding,” says STEM Coordinator Lynn Panther, “this is a strategy we are putting into practice as often as we can.”

Evaluating instruction has been a focus for Chehalis teachers as they work to improve their skills. For four years, the math teachers have been working with researchers at the University of Washington for this very purpose. “With the Math 360 Project, educators from Chehalis and UW learn from each other, and share,” says Director of Student Achievement Rick Goble. “Really, it’s action research we are doing together.”

Last month, UW professors observed every math teacher at the middle school and high school. Caty Lieseke, a teacher at W. F. West appreciated their feedback. It was quite positive, and specific. “The introductory estimation activity (travel time in an elevator),” they said, “was a good way to get students thinking individually first, then sharing together, and to have them consider their assumptions.”

“Another thing we noticed is just how beautiful a job you do of not evaluating students’ ideas as right or wrong. You so purposefully call on a number of students to share their ideas – and there is no hint in your tone or response as to what is correct.”

This is classic mathematical discourse. Teachers facilitate conversation, and learn how to ask the right question in the right way to foster deeper discussion. Lieseke appears to be great at this strategy. “We loved being in your classroom,” said the visitors from UW, “and seeing how you connect so deeply with your students, and for sharing your love of mathematics with them (and us).”

“My colleagues from the University of Washington were very affirming of the work I am doing,” responded Lieseke. “My math class should be a place students can challenge themselves educationally, and belong socially.” The focus on community-building is quite intentional. Ms. Lieseke schedules time to practice discourse on less challenging content just to give students practice in listening to others, and sharing thoughts. Students need time to practice sharing their thoughts with supporting details. They need experience evaluating their line of thinking against someone else’s and having the chance to self-correct.

For example, she will ask students to solve the following: 543 – 245. Students can’t use calculators or pencils, or even talk with each other. Then they share their answers aloud and explain how they arrived at their answer. Lieseke recalls one student sharing, “Originally I got 198. I know that it’s wrong, I just want to explain how I got it.” This chance to talk about the process provides what Lieseke calls, “Door Openers.” It’s at this point she can ensure learners know the correct answer and evaluate their thinking – in a safe environment.

Using mathematical discourse in the classroom helps learners find how math makes sense to them. “Making their thinking clear to others in the room helps students make sense of what they are learning – they own the learning and their understanding,” says Lieseke. “It’s not just what the teacher said.”

“This is all just part of the journey students take in the Chehalis School District,” says Goble. “Teachers PREPARE, students ENGAGE, teachers ASSESS, students IMPROVE, everyone PERSEVERES, and as a result, students ACHIEVE.

Learn more about how Chehalis educators prepare students for their learning journey by visiting the district website at chehalisschools.org/sai/